“Can’t push a rope up hill.”

“You can teach whoa, but you can’t teach go.”

“Easier to peel it off than to put it on.”

These are just a few of the cliches I’ve heard about starting pups over the years. This sort of colloquial wisdom survives the ages for a reason, because its true. I rarely see a problem dog that has been well exposed to the general world and has been allowed to move with freedom in the field. I do however, see plenty of young dogs that a wary of new environments and soft to any and all handling. There are a (proverbial) million articles and videos teaching you how to train your bird dog, but there is very little content admonishing us to temper our influence on our pups and let them experience all that this big new world has to offer. There are rocks and creeks, frogs and crickets, timber and fields …and there are birds!

I am not sure how many times I’ve read facebook posts soliciting advice for a pup that is flash pointing and running birds up, or even worse (gasp) catching. The comments section of such posts is undoubtedly full of “time to stop him chasing”, “time to teach whoa”, and the ever present “NEVER LET THEM CATCH!” This all runs so oddly contrary to the words my Grandpa said in response to me informing him that I was going to hang a shingle as a pro trainer, “That’s the dumbest shit I’ve ever heard” (referring to this supposed demand for professional bird dog trainers). You just turn ‘em loose, they’re either a bird dog or they ain’t.” You see, in Grandpa’s day there were enough wild birds to make a serviceable bird dog with very little training. Today, most of us, at least in the southeast US, are limited to pen-raised bobwhites and pigeons in launchers. We simply cannot count on the wild birds of our Grandfathers to turn our pups into refined pointing dogs.

In other traditions of training, namely police and protection sports puppyhood is a time for “making monsters” (Bradshaw and Siggins, 2012). It is a time to guide your puppy towards confidence and boldness of character. It is a time that is less about refinement and more about power and strength of will. Even those looking to end up with the most gentle of companion gun dogs appreciate style and grace in the field. These traits don’t simply appear; they are the result of drive and determination, of anticipation and frustration in earlier training. Most dog folks I know generally agree that pointing is a “refined” stalking instinct. The refinement is the result of hundreds, if not thousands of generations of selection for that specific trait. It is coded into our dogs’ DNA. It doesn’t simply dissolve if our puppy is allowed to chase or even catch a few birds.

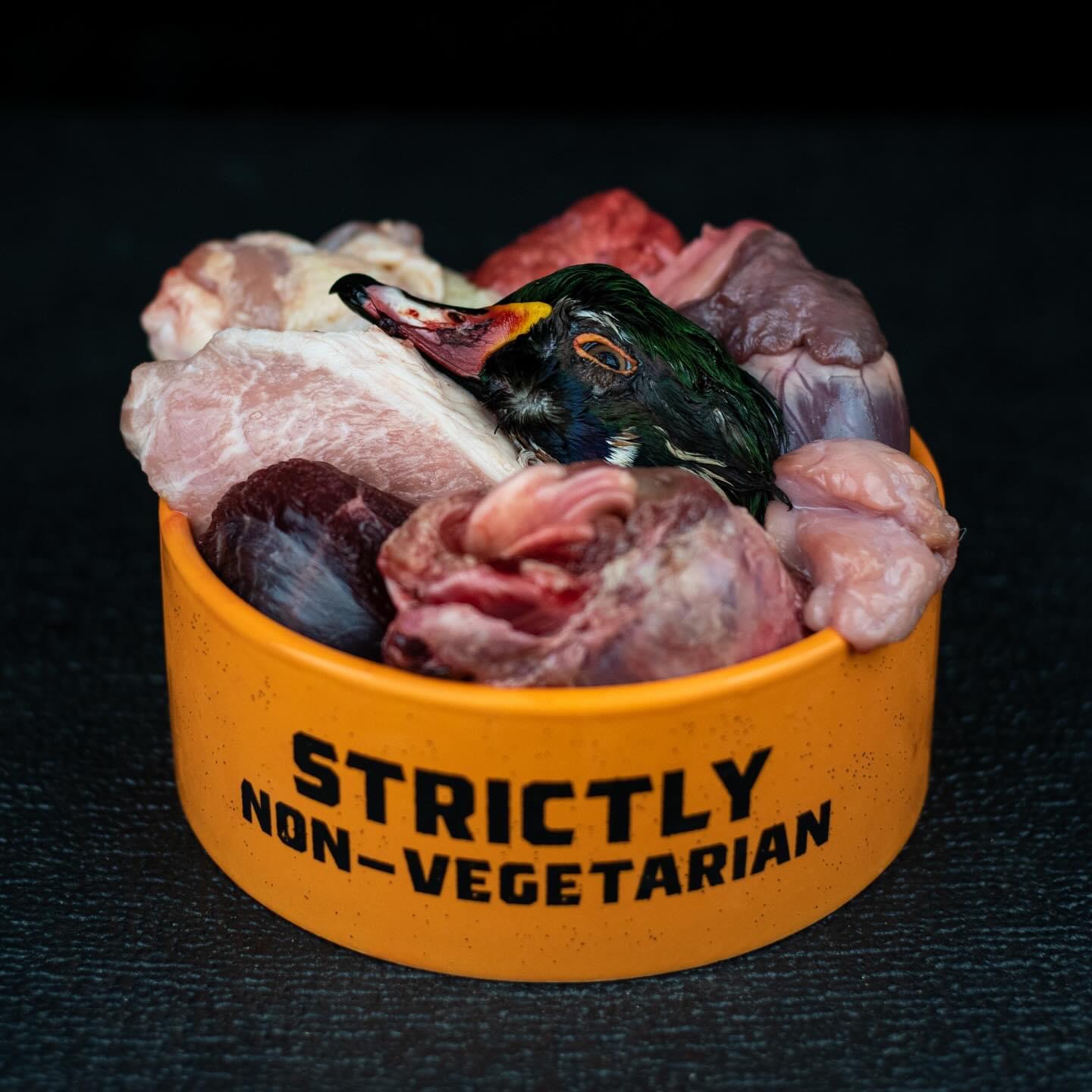

On more than a few occasions I’ve been tasked with “rehabilitating” a young dog that is blinking. Often times it is simply a matter of winding back the clock and letting them experience a wild and reckless puppyhood. They’ll be given dozens of cripples to chase and catch, and as they’re confidence grows so will the bird’s ability to escape them, until eventually the birds cannot be caught and must be stalked and pointed. We have made our monsters in the field and now we have something to work with. The chase, capture, and possession of the game then becomes a tool for us to present the dog in order to reinforce gradually increased criteria for “bird manners”.

For me, there are no exceptions to the rule for puppy development. Here pups will be allowed to chase and yes, even catch their birds until I think they are ready for the birds to start eluding them. This doesn’t mean that I can’t begin to require manners from them at home. The crate, a strict routine, and a classically conditioned “no” will always be in play for my house dog prospects. They’re usually plenty capable of understanding context and distinguishing between expectations in the field and home.

There are trainers that I respect that will likely disagree with this article and that’s okay. “Variety is the spice of life.” “There’s more than one way to skin a cat.” “Opinions are like…” I’m sure you get the idea.